There have been iconic moments in the history of medicine. We learn about some of them in medical school and through the writings of historians. For instance a year or two ago I enjoyed “The Butchering Art,” a wonderful book on Dr. Joseph Lister and his fight against surgical infections, by medical historian Lindsay Fitzharris. (I highly recommend it.)

https://www.amazon.com/Butchering-Art-Transform-Victorian-Medicine/dp/0374117292

Of course there were plenty of such critical transformations that came early in the modern era, or predated the modern era. There were no doubt many that came well before the very invention of writing. There were ‘physicians’ long before our complicated educational processes, degrees and certifications. In the ground lie doctors and patients from down the eons, whose names we will never utter in this life.

While those physicians lacked our enormous scientific capacity, and while their patients suffered from staggering death rates from things we take for granted as survivable, their professional lives might have been delightful if only for the fact that they were not entangled endlessly in the bureaucracy, the regulations, the finances, even the electronics of modern healthcare.

So, I began to wonder, what would it have been like if they were faced with the madness of modern healthcare?

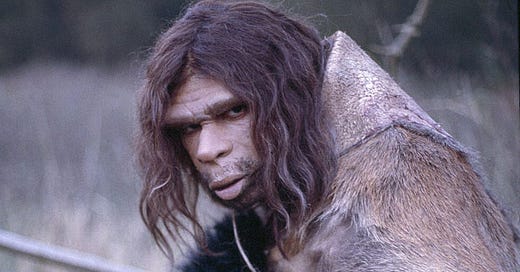

Picture a European cave and a band of Neanderthals. (Who apparently cared quite well for their sick.) One has been chewed by a Cave Bear. His friend sees the blood spurting from his cousin’s leg onto the wall of his cave. It occurs to him that ropes with slip knots get tight on limbs. Somewhere he makes an association and decides to apply the first tourniquet. As he cinches it down:

‘Pardon me sir, that intervention has not been approved by a placebo controlled, double blinded study and is in NO way approved by the Neolithic Agency for Herbs and Trepanation. You are forbidden to use untested and unproven interventions. By the way, where is your medical license?’

‘But cousin die!’

‘I understand, and it gives me no pleasure, but rules are rules!’

Now, fast forward.

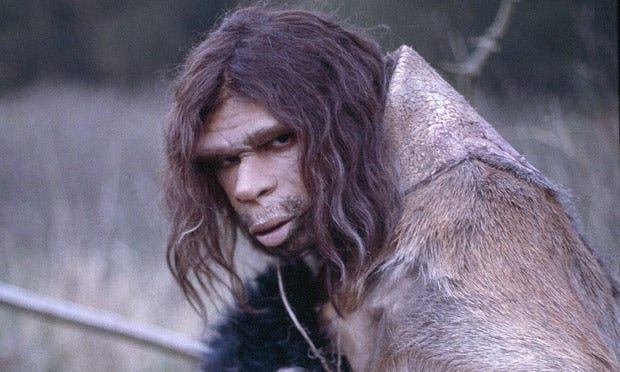

I’m picturing an early epidemic, maybe in ancient Egypt.

A physician, well educated by the standards of the day, steps between the suffering bodies of the dying. Turning to his assistant, he asks for parchment and sits to describe the situation and send to Alexandria for supplies. As he puts ink to paper administration arrives:

‘Pardon me doctor, but I trust you are aware that it is strictly forbidden for you to use the names or locations of these patients in correspondence without their expressed consent. Furthermore, you cannot use that parchment without telling me the encoded password that demonstrates that you are the appropriate physician to document and write orders.’

‘There is no other physician here. And all of these people are unconscious and dying. What is a password?’

‘I suppose you haven’t done your latest education module, but let me make it simple. These patients may be dying but are doing it with their privacy protected and their dignity intact, sir!’

Moving on:

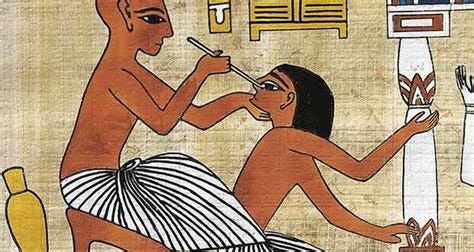

Poor King Harold lies dead on the field of Hastings, maybe from an arrow through the eye-socket, as displayed in the famed Bayeux Tapestry. Alas for the end of the Anglo-Saxon era, mourned by those of us who are likely descended from those people groups.

His men are fleeing as William the Conqueror wins the day. One of Harold’s nobles (we’ll call him Earl Edwin of Northumbria for no particular reason) has fallen. He is struggling to breath, a Norman spear point having passed through his armor and through his chest. A kind Norman physician, also a priest, sees him on the battlefield and comes to offer aid. Kneeling, with kindness in his eyes, he offers prayer, then asks:

‘Can you please complete these forms and offer two forms of identification? Will you also please fill out this consent form?’

‘The Earl nor I can read or write, kind sir,’ says the servant who in messy Latin.

‘Pity. Well, make an X. And just go back to the waiting room. We’ll call in a bit once we figure this out.’

Earl Edwin expires wondering what ‘waiting room’ means. His servant is summarily butchered, of course.

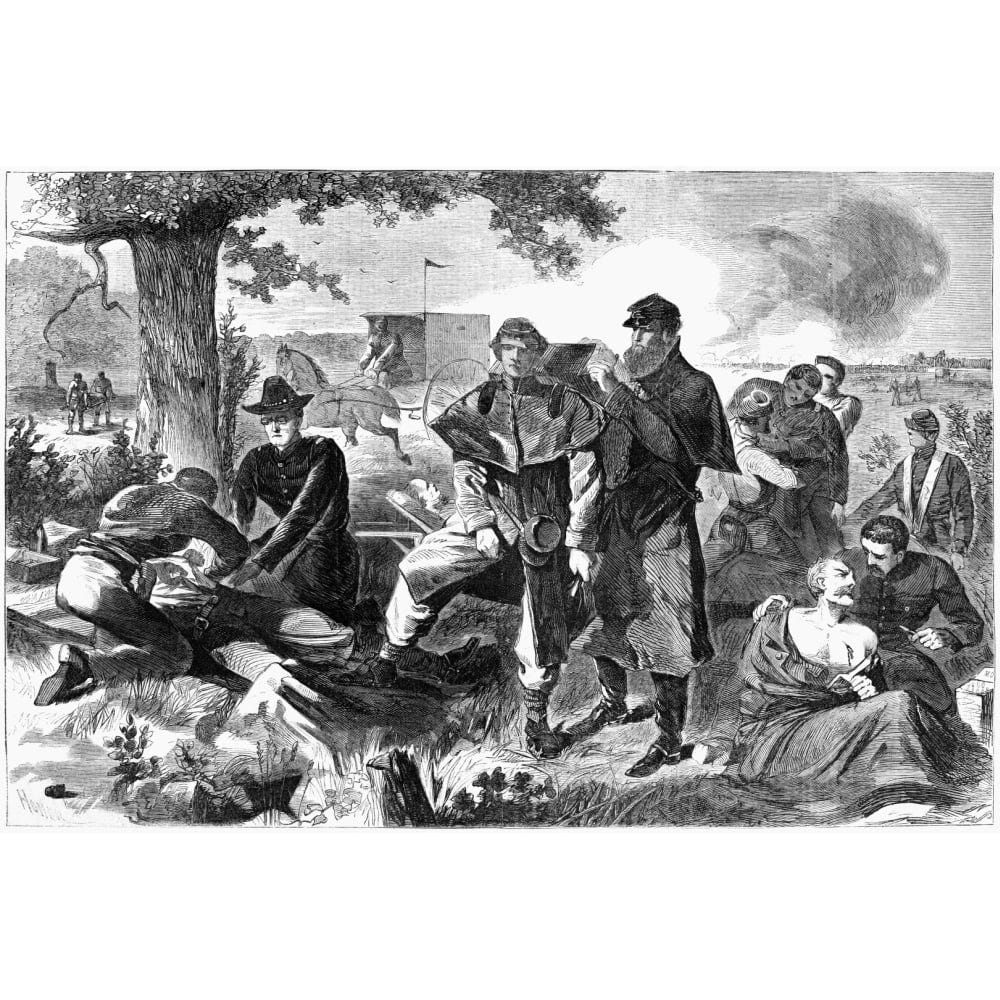

And what scenario would be complete without considering the devastation of the Civil War, where blood ran in rivers and limbs were stacked by the thousands.

We’re at Antietam, the single bloodiest day in US History, with 22,727 dead, wounded or missing.

In his tent, Federal surgeon Wilfred Mahoney stands ready to remove the shattered leg of a Capt. Joshua Hagood, US Cavalry, brought in by stretcher bearers after he was struck by a glancing cannon ball.

There is some chloroform available, so Capt. Hagood will not have to endure the procedure awake as so many have down the steady but brutal ages of developing surgery.

The line of wounded is long, the flies buzz in the September heat, the smell of death rises and the moans and screams tell Dr. Mahoney that he will operate long into the night.

As he begins to prepare and administer the anesthetic:

‘Whoa there doctor! You can’t take off a man’s leg without a time-out! I mean, is this the patient? Is this the correct leg? I’m from the patient safety office and I have terrible concerns. I mean, do you have a list of this man’s medications and is he fully aware of the risks?’

‘Well, he has two legs and one of them is nearly shot off. That seems like the right one. Captain, do you take medicine besides whisky and cigars? Do you want me to do this?’

‘NO I don’t take anything and no, I mean yes, for heaven’s sake man put me to sleep and take away that leg. It’s killing me!’

‘Well, doctor, until you have completed a formal time out and the required forms, I can’t allow you to proceed. I’ve half a mind to shut down this entire operating suite until we can do a training session!’

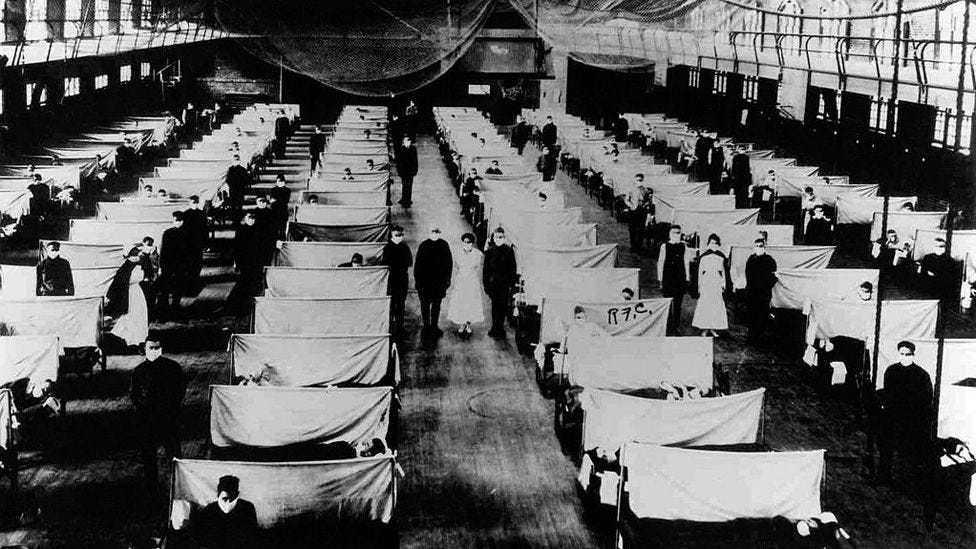

And who could forget the terrors of the 1918 Influenza epidemic (misnamed the Spanish Flu). Young people, otherwise healthy, became ill and died in a few days of overwhelming respiratory failure.

I imagine a team staffing it, all day and all night, exhausted from sheer fatigue and from the enormity of the death and grief all around.

They are sitting together in a small office, trying to organize their shifts, running for water and food, changing bed-sheets, cataloging the dead, writing letters for the dying, trying to drink coffee or smoke to stay awake.

‘Everyone, please pay attention! Our survey team is here and all food and drink has to be put up for the next 12 hours. And for heaven’s sake, there’s no smoking on the grounds here! Also, please put away your jackets, bags and purses. We don’t want any negative reports, do we?’

Nurse Hudson chimes in: ‘Ma’am, we have been awake for almost 24 hours and all that we can do is drink coffee, take a drag and eat a sandwich every now and then to keep up our strength. Two of our staff died last week and two more are ill. We don’t have enough of anything!’

‘Well I understand but you’ll just have to do your best. And please don’t say anything to the surveyors or patients about being out of equipment or being overwhelmed. It just sends a bad message. We’ll talk about proper communication next week at our safety huddle, k?’

I could go on. Maybe about ancient physicians subject to modern rules who spent more time carving tablets than ministering to the sick. Or about good ‘physicians’ being told that they couldn’t work in the next city-state due to non-compete clauses. What if the fear of malpractice litigation prevented every great surgeon in history from exploring new options, from opening the chest or abdomen (a thing simply not done much until the 19th century) to putting rods in bones and all the rest?

We could talk about physicians who would love to treat the battlefield wounded but haven’t been able to provide a list of all of their procedures for five years, the addresses of their prior employers or exact dates of all of their educational endeavors.

Fortunately, the silliness that we face in healthcare today was not present in most of the the long, slow birth of the science of medicine. Some of it was chaotic, some of it was wrong, but the goal was clear and the relationship and duty between physicians and patients was paramount.

Imagine if polio vaccines, as important as insulin, were controlled by large corporate interests and cost ridiculous amounts of money such that the poor simply suffered from polio. Imagine if young doctors in early modern medical centers spent far more time writing in notebooks than touching patients and learning procedures. Where would we be now? How much knowledge would we lack?

Imagine if nothing mattered as much as the chart and the associated bill? Oh wait, that’s what happens now.

I hope that one day we can go back to the right focus, the right hierarchy, and treat people efficiently and well.

Until them, our medical ancestors probably look down and shake their heads at what has become of us all.

I enjoyed reading “The Butchering Art” immensely. But the challenge then and now is to get folks to agree on how to move forward. Politics have always muddied the waters.

Be the change we wish to become. Until far far more physicians embrace the ineluctable linkage between a multiple payer system predicated by employment, or retirement, there will be no progress. Physicians have to be the catalyst, but far too many of our colleagues, whether It’s ten or forty cent, went into medicine to ‘make money’ and this is what we have wrought. How else to explain the great majority of physicians vote for republican low tax and free market solutions to everything, including health care (I’m confident they would defund public eduction and social security if they could). There will be a revolution in how we finance health care; it can't go on this way forever. But physicians are now mired in battles over credentialing and distracted, and too many of us -yes I’m talking about you proceduralists, are still making huge money and on the golf course 2 days a week. However, no,politician goes blameless in this disaster. The trial lawyers will oppose any move toward public financing of health care-where will the deep pockets be to sue once we have no fault government health insurance? A good place to start is simply extend medicaid to all children under the age of 18. Talk about low hanging fruit…What a moral and public health victory that would be , at very minimal cost. But it is the camel inside the tent isn’t it?