We live in the northwest corner of South Carolina, in Oconee County. We are solidly in Appalachia, as far from the sunny Carolina coast as you can get and still remain in the Palmetto State. (As I’ve noted, West Virginia natives are drawn to SC like moths to a flame.)

We’re very close to Greenville, SC and Asheville, NC, where the storm hit with incredible fury. We lost power but fortunately still had our cell phone service.

Watching the devastation of the storm is heart-rending. First because of the scale of human tragedy, and second because we have driven past these places, have loved their beauty and their people. Here is Unicoi County Hospital, in Tennessee. I once inquired about working here because it seemed like a garden spot as hospitals go. I wonder if it will ever re-open. Staff were carrying patients to the roof on their backs in order to be evacuated by helicopter.

I have spent most of my career working in emergency departments in Appalachia. As such, I have some thoughts based on my understanding of disasters, of emergency medical care and of Appalachia itself.

I don’t need to say anything about rescue, or traumatic injuries. That’s a given and there are true, courageous experts on the ground like my friends, Steve Pack, paramedic and white water expert, Brady Kay, RN in an Asheville ER, and Seth Collings Hawkins, emergency physician and wilderness medicine guru.

However since medicine has changed, and patients have changed, in the 31 years of my career, I believe that there are some issues that need to be discussed. If not relevant to the current disaster (as we always “fight the last war”), these thoughts may be relevant to some future planner.

I recently wrote about how medically fragile many Americans are these days. I published it here, but then published a more lean version at MedPage Today, if you’re interested.

https://www.medpagetoday.com/opinion/rural/111998

That medical fragility makes the disaster response more complicated. Appalachia, which is my beloved home, is also a place of many health challenges. From diabetes to addiction, from cancer to heart disease, the list is long and difficult to manage.

There are many very sick, very fragile individuals who are dying and still in need of rescue. Here are some examples of the challenges this disaster creates, in no particular order:

It is imperative that renal failure patients on dialysis actually make it to dialysis. They typically go three times each week. Many require ambulances or at least friends or family to transport them. A few days without dialysis is very dangerous. They typically have a host of other medical problems associated with their renal issues so time is of the essence.

Cancer patients or those with complicated infections often need their regularly scheduled infusions of chemotherapy agents or antibiotics. In Appalachia, these people don’t usually live downtown in accessible apartments. They may live at the end of Rock Springs Road, or up in Copperhead Valley, across two narrow bridges that have already washed away.

Diabetic patients need insulin. And it’s typically difficult to get a “supply” of insulin due to the ridiculously high cost. Furthermore it has to be kept cool. Without power the refrigerator won’t stay cool long and the ice won’t stay ice long. And thus, the sugar won’t stay low long. Insulin dependent diabetics without their medication develop diabetic ketoacidosis, which can easily be fatal and often requires care in an ICU. (This is of particular interest to me as father of an adult diabetic son.)

Some individuals who might self-rescue to neighbors or main roads are unable to do so because they are old, frail and weak from stroke or dementia. Some have no family, or family may be likewise geographically isolated from them. With the amount of water that swept through these hollows, with the downed trees, labyrinthine brush, mud and washed out roads, even half a mile can seem an insurmountable distance.

Others are fully wheelchair or bed bound. Some are simply too obese to move without help. These people are in dire straights and can only count on the help of those close by until professionals arrive.

The unfortunate reality of hoarding makes all of this more complicated as individuals may not only be trapped by water but by water-soaked and displaced “flotsam and jetsam,” making all rescue efforts more difficult. (And contributing to the proliferation of hidden insects, reptiles and mammals.)

Those on oxygen for the ubiquitous chronic lung disease of Appalachia have limited supplies. Some have swapped tanks for oxygen concentrator devices which require electricity.

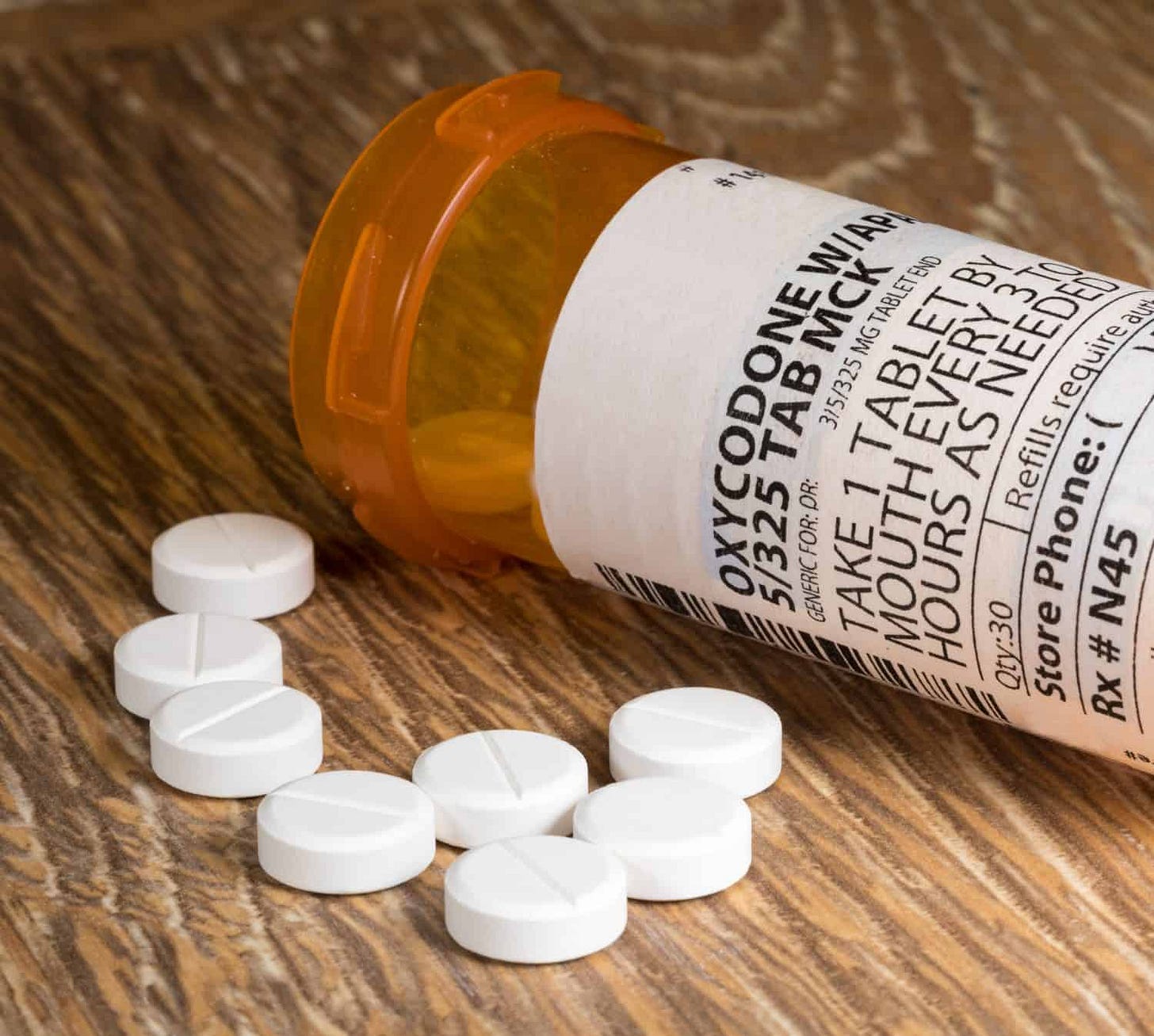

Of extraordinary importance is the issue of pain control. While it can seem like a secondary concern in the big picture, it reallly isn’t. Those with chronic pain, such as the pain of rheumatoid arthritis, spinal injury, cancer and other conditions count on pain relief.

Without access to refills, to open and functioning pharmacies, this is what many will face. Patients with terrible pain and loved ones unable to help and feeling frustrated and angry. For decades now we have emphasized the importance of pain control. Medical care and patient satisfaction seem built around the pain scale (for better or worse). That simply can’t be dismissed during a disaster. (“Oh, pain, that’s not a problem now.”)

The opposite side of this issue is that there will be many who are unable to obtain fentanyl, methamphetamine or other substances to which they are addicted. Withdrawal from stimulants and opioids is miserable and may produce desperate behaviors. Withdrawal from benzodiazepines (think Valium, Xanax, Ativan, Klonopin) can be fatal.

The same is true for alcohol withdrawal. Will alcoholics be able to obtain alcohol? Especially with stores closed? Unlikely, especially since many are poor and won’t have stockpiles put back.

Nicotine withdrawal is also miserable and makes people who are already at wit’s end more agitated…and perhaps more desperate.

It is an understatement to say that the homeless will pose unique problems, as many are also addicted or suffering from severe, undertreated mental illness. They are vulnerable to disease and weather (and violence) in ways that others are not.

Refills of all sorts of medicines will matter. Diuretics for heart failure, antihypertensives, oral medications for diabetes, medications for seizure control, anticoagulants for heart disease, blood clot or stroke prevention, etc. The list is long.

Also, without power or water, hygiene will become problematic. When family, friends or home health workers can’t come by those stuck in bed will inevitably be stuck in their own waste.

Of course, as we learned locally, electronic payments won’t work. In the days of the debit card, in the days when some want us to be fully cashless, our local grocery store is cash only. This is because their corporate headquarters is also underwater. How many people keep a lot of cash aside? Fewer and fewer. So those without cash, who need things like water, ice, food, medications and clearning supplies, won’t be able to obtain them even when stores are open and people can get to said stores. (Our northern European ancestors often wore gold or silver jewelry because it could be cut up as currency. Maybe that’s not a bad idea.)

We were watching the news from Asheville yesterday and a public health authority was saying that if anyone had questions they could call for guidance or log onto the public health website. And yet, most people lost cell service and internet early in the storm. Furthermore, without power cell phones and computers die. (Fortunately my wife wisely bought us solar chargers a while back.) To make all of this worse, some seniors are often unable to navigate the Internet, or their phones, on a good day. It’s an understandable statement by public health as everything seems to be online now, but it is not relevant when victims have no way to communicate whatsoever.

(Which also means, as we move from land lines to cell phones only, that those in need of 911 asssistance simply can’t get it because their phones won’t work.)

Soon enough, infectious diseases will likely emerge due to the fact that it’s still very warm in the south, insects abound, hygiene is poor to nonexistant and refugees will be in close proximity in hospital waiting rooms or shelters.

Look for clusters of flu, COVID, meningitis, pneumonia, perhaps encephalitis and certainly intestinal illness. Also, wounds in feet from immersion in dirty water (think combat trench foot) may also develop.

Normal, day to day care of car crashes, strokes, heart attacks and everything else will be disrupted as ERs will be full of those displaced and seeking care for the things I’ve listed above, as well as for injuries sustained while performing rescue and reclamation. Expect long, and I mean long, wait times.

Finally we have to remember that this is also a mental health event. Those with chronic mental illness will be especially distressed.

But those who are responding, those overwhelmed with human suffering and need, those extricating the dying and dead, they’ll need our help. Hospitals, EMS, fire and law enforcement groups and churches all need to pay close attention as this is a massive generator of PTSD. Y’all just keep it in mind. And if you need help, don’t be ashamed. This is like nothing most have ever seen.

I haven’t been directly involved in disaster planning for many years, but a few things come to mind.

The preppers weren’t crazy, they were spot-on. Food, water, generators, medications, etc. are life saving.

Every EMS system and every community should keep a list of those who are especially vulnerable, whether children or adults. We should know where new moms and babies are and where the aged and infirm are to be found. The time for internet based self-sufficiency is long past. We need to care for each other. (The lagging federal response is ample evidence of the truism that “nobody is coming to help you.”)

We can’t rely soley on cell-signals to get critical help. (But thank God for Starlink…) Land lines should make a return. CB radios might be an option. Those so inclined, especially perhaps those with limited mobility or health/fitness, would be well served to learn how to do Ham radio in order to expedite communication for communities.

Rescue in these heavily forested mountains, narrow valleys and endless small and large watercourses is complicated and dangerous. Props to all of those who are out there engaged in it. I continue to pray for their safety and success.

Jan is recuperating from her recent 12 day hospitalization for severe pancreatitis. We’re so sad that we can’t currently be part of the response. However, I fear there will be ample needs as recovery will take years.

We had a few days of anxiety about our firstborn, Sam, who lives and works just north of Asheville. He had no power or cell-service but he and his friends are a mountain tribe and took care of one another. He and a friend, Alex, made their way to us three days ago for shower, food and resupply with water and gasoline. They both work at Navitat Zip Lines, and are comfortable with handling nature in her vagaries.

https://navitat.com/asheville-nc/

I’m sure there are things I’m missing so feel free to supplement in the comments.

I’ll close with this. Appalachian people are our people; resilient and determined, descended from immigrant pioneers and generally fearless. They’ve been isolating and prepping since the French and Indian War.

But Appalachia herself, numinous, ancient as Saturn’s rings, older than trees as we know them, can be a malevolent bitch. Never underestimate her ability to cause surprising devastation.

Always, always respect her.

And take care of yourselves and one another.

Edwin

As always, you bring enlightenment to a heavy subject. My heart is heavy for Appalachia; praying for your wife's recovery as well. (Pancreatitis is miserable and difficult to recover from.) Reagedinf the logistics nightmare, I had the very same thoughts: so many people will have unthinkable consequences from all of this devastation. I have long maintained that the healthcare system was far too dependent on technology; the idea of "portable" records is fine, as long as the power grid holds up. Not sustainable at all. And being dependent on computers and digital devices for payment is useless when there's no power to be had, as you noted.

My husband was an Eagle Scout and an avid camper for years. He happens to be a "prepper". And the more we hear and see of disasters occurring, the more we realize we had best be as prepared for the long haul as possible.

New Yorker here, do you have any organizations that you would especially recommend donating to?