When I started my college career I intended to be a magazine journalist. I read magazines like National Geographic and U.S. News and World Report and loved the flow of the stories. Marshall University was known as an excellent journalism school, and my junior high and high school English teachers (Mrs. Diane Chandler and Mrs. Maggie McCarty) had supplied me with a solid set of writing skills. I used to think I wanted to be a foreign correspondent or maybe a war correspondent.

The path I took from there to the house of medicine is a topic for another day. Nevertheless, I eventually returned to writing and sometimes feel as if I did end up a foreign correspondent. Mainly because medicine looks so different from the way it did in the halcyon days of my early career that it sometimes resembles a foreign country. (1)

And some days, when the emergency room is full, the hallways are stacked with people, the overdose patient is blue, there are no inpatient beds and no ambulances to transport our transfers, well it has some of the chaos I imagine I might have been reporting on in some third world war-zone. (Albeit, without the imminent threat of mortars or automatic weapons.)

It’s good writing material, this madness of medicine. There’s hardly a day that goes by when I don’t have an interaction that makes me want to tell a story of staff silliness, highlight an issue with the system or simply say something about the human condition.

So having cleared my throat for several paragraphs, I’ll say that things have changed over the past 31 years that I have been in practice. It’s multifactorial, and it’s hard to define, but there has been a shift.

These days many young physicians who work in emergency medicine (and indeed other specialties) are seeking an exit from the job after only a few years. I see their posts on social media, I talk to them at meetings. They’re already exhausted. No, they’re already defeated. I used to think, “I’m an old man and I’m still at it! What’s wrong with kids these days!” (I’m one of the last of the Boomers, so you’ll have to excuse the surly attitude. I usually reserve my venom for communists.)

The more I thought about it, the more I understood. My career was shaped in a time when we, as physicians, had more control; and hope. The physician group I belonged to for my first twenty years ran our own business, our own staffing, our own billing and our own schedule. We were friends, brothers and sisters, and we cared about one another.

Physicians now are increasingly employed by large, for profit (or so-called “not for profit” which are really for profit) hospital systems or staffing companies. They have little to no control over the life they worked for, became indebted to attain, and dreamt of over years in the library and at the bedside. That’s demoralizing.

They’ve also been swept up in the madness of customer satisfaction and the tyranny of electronic medical records and all of the metrics we have to follow in order to be paid. (Time to a room, time to an EKG, time to antibiotics, time to admission…) Physicians now are under the thumb of ten thousand people, who depend on their income and make rules to try increase that income for the system. (Hospital gift shops and cafeterias are not profit centers, so it’s patient care that brings in the money.)

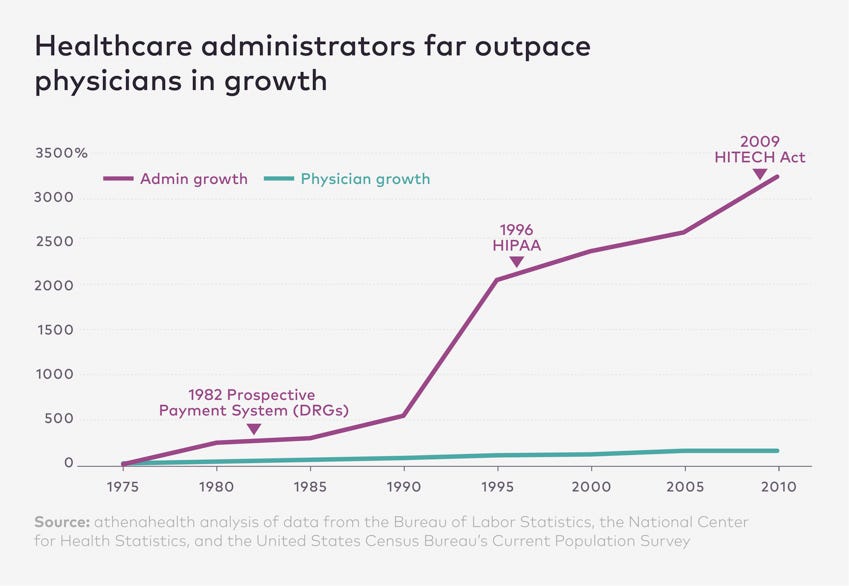

This graph has been around for a while. It certainly feels correct. I suspect both lines have continued in much the same direction.

But it isn’t just the culture. There’s something about the biology of medicine. Sepsis is a great example.(2) While we’ve done a wonderful job finding and treating people with life-threatening sepsis, the result is that we have a lot more old, sick patients who (in decades past) would have died. And in the process we would have had more rooms, both in the hospital and in nursing homes, for the surviors. The same is true of strokes, heart attacks, lung disease, congestive heart failure and the other entities that not so long ago were inevitably fatal in short order. (In decades past pneumonia was often referred to as “the old person’s friend” because it took them when they were at the end of life and struggling with other issues.)

Now please understand, I’m glad we do what we do. Everytime we do better we push the envelope of medicine. And while some folks who survive serious illnesses struggle with normal lives, others make full recoveries. In time our progress will continue. More and more people will not only survive but thrive. That’s a worthy goal. But until then? That’s the problem.

Right now physicians are faced with unique clinical problems. Because we seem to have transcended our ability to care for some of these people. Maybe a better way to look at it is that physicians often seem to be dealing whole new kind of biology. We have people who have failing hearts and failing kidneys, in whom balancing medications is tenuous, with their systems working in a very narrow range that falls out of function easily, requiring frequent hospitalization.

Cardiac interventions have saved countless lives. Men and women who would have perished from heart attack get stents placed in occluded vessels and go home. But sometimes their cardiac function is compromised and their heart muscle, and heart rhythms, can be difficult to manage.

We have patients of very large size who are often too large to put into CT scanners and who are very difficult surgical patients. Even examination can be difficult. Understanding the physiology of a person who is extremely obese can be challenging at best.

Some of our patients have liver disease, both alcoholic and non-alcoholic, which also requires a delicate balance of medications to keep them functioning, and often results in procedures to take fluid from their abdominal cavities; fluid which can become infected causing sepsis. Meanwhile the ammonia that they cannot process with sick livers makes them confused and agitated, but their blood pressures may be too low for sedation.

Drug abuse has ravaged generations, and in particular the injection of fentanyl and methamphetamine cause complicated infections in spinal cords, extremities, cardiac valves and well, every part of the body. To make it worse, these patients have often exhausted all of their IV access requiring large lines in central veins in their legs and chests. But, send them home with a permanent IV port and they are at risk of injecting their drugs of choice. These patients are notoriously septic but too often leave the hospital early because of the affliction of their addiction.

Without psychiatrists, and sometimes with them, we have no idea how to manage the complicated interaction of mental illness with assorted drugs, including everyone’s darling, marijuna. What will marijuana and its assorted products do to health in the future? It’s hard to say but I predict more schizophrenia, and more heart disease and cancer from those who smoke it.(3) My point being, however, the potential effects of street drugs on those with underlying mental illness (and simultanous lung, liver, heart and kidney disease) are extraordinarly complicated.

Of course, all of this is complicated by the addition of new medications, which can be great in their own right, but which have side-effects and interactions that we’re only just seeing and understanding. GLP-1 agonists like Semiglutide are a great example. Hardly a week goes by that we don’t see complications, as well as successes, with this class of drugs.

While I don’t see this in my area, the complexities of gender transition surgeries are doubtless very difficult for those who care for those patients, not only on in regards to their procedures but I imagine also when they have other illnesses, or have injuries requiring surgery.

This is all added to the constant, ongoing parade of death by tobacco and alcohol, which kill in so many ways, and yet continue to rob men and women of decades of life through the power of addiction. And both of which make human physiology and disease that much more complicated; especially in those who already have survived serious illness.

I could go on and on. But a reader of another column of mine, on a similar topic, described our patients now as living “on the knife’s edge of homeostasis.” I couldn’t have said it better.

But there’s a third factor here; no a third and a fourth. Our hospital systems, in particular those administrations that hoped to make great profits, have run into a wall. The patients, the payers, they wanted have arrived in vast numbers. But they are so sick that they cannot stay out of the hospital long. They are so complicated that their care demands enormous resources in staffing and material. And after a while, they are out of money or their insurers, such as they may be, can scarcely afford what the patients need. Insurers? How long can they maintain this veritable nation of fragile humans? I can’t imagine it will last more than ten more years at the current pace.

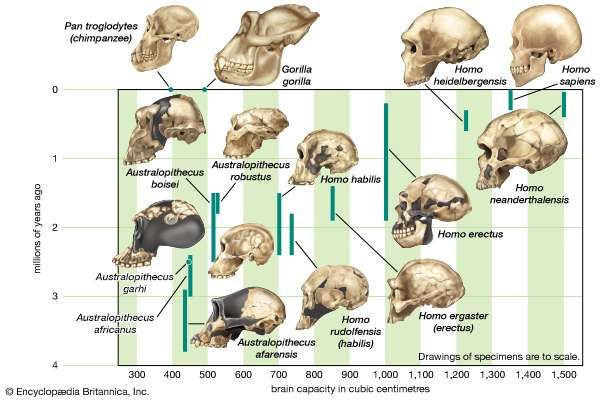

I realized, reflecting on all of this, that we’ve almost created a new species. Humans are known as Homo sapiens, thinking man. But we seem to have rapidly transformed a subset of our population into Homo infirmus, sick man. Or maybe better, Homo fragilis, fragile man.

Homo infirmus is increasingly dependent on a healthcare system that can ill provide people, drugs, space or equipment. And we have become so fragile that we cannot long survive without it.

Maybe this is why our shifts feel so overwhelming. Maybe this is why my young colleagues already have that look in their eyes.

They’re practicing traditional medicine on an entirely different kind of human being, in a system that never expected such successes and never planned for the survival, complexity and in some cases, poor health (through bad luck or bad choices) of those dependent on it.

My colleagues and I are now held to a standard of care, and an expectation of medical success, that nothing really prepared us to face. And we’re doing it in a system that really planned mainly for profit and isn’t up to the task at hand.

Welcome to Emergistan, the land of Homo fragilis. Where all of the old rules of biology and the business of medicine are slowly fading away and nothing works the way it should.

I hope we can figure it out before its my turn on the stretcher.

(1) My regular, monthly column in Emergency Medicine News over the past 20 years is titled “Life in Emergistan.” Here are the archives: https://journals.lww.com/em-news/Pages/collectiondetails.aspx?TopicalCollectionId=6)

(2) https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/sepsis/symptoms-causes/syc-20351214

Edwin, I’m PGY 41 and still at it and love EM but, like you, I hate what non medical administrators have done to it. You have a tremendous gift to express all of our frustrations.

God bless you and all of us on the frontlines.

Dr Jim

Great comment, as usual. A few thoughts, especially related to this column. We don’t save lives; we postpone death. I have often described emergency physicians as conductors on the train of life, which is a one way journey. Our job is to try to prevent fellow passengers from getting off prematurely. We do not, in many ways, do a service to our patients if in improving the quantity of life we markedly diminish the quality. I see many of the wonderful, yet phenomenally expensive new medications (often heavily advertised on television) touting a “significant improvement” over current regimens. Significant, yes, but almost always statistically significant (sometimes as little as two months longer survival, on average) rather than clinically significant, disease oriented rather than patient oriented. A new anti-hypertensive medication may lower the average systolic pressure by 4 mm over a large population, but if it doesn’t reduce the incidence of heart disease, kidney disease, or strokes, so what. Statistically significant but not clinically, seems to be what is in the ads and clinical papers. Preventive medicine is where it should be. The most dangerous substances in our society - tobacco, opiates and stimulants, alcohol, too much salt and sugar, and dangerous behaviors (not wearing seat belts, driving too fast and/or while impaired (and too many overly tired physicians in training), ignoring preventive immunizations, etc. The loss of productive years from premature deaths due to Covid and drug overdoses is terribly sad, and a huge loss for our society. We are fragile; I love the term, and knife edge of homeostasis. Thanks for educating us.